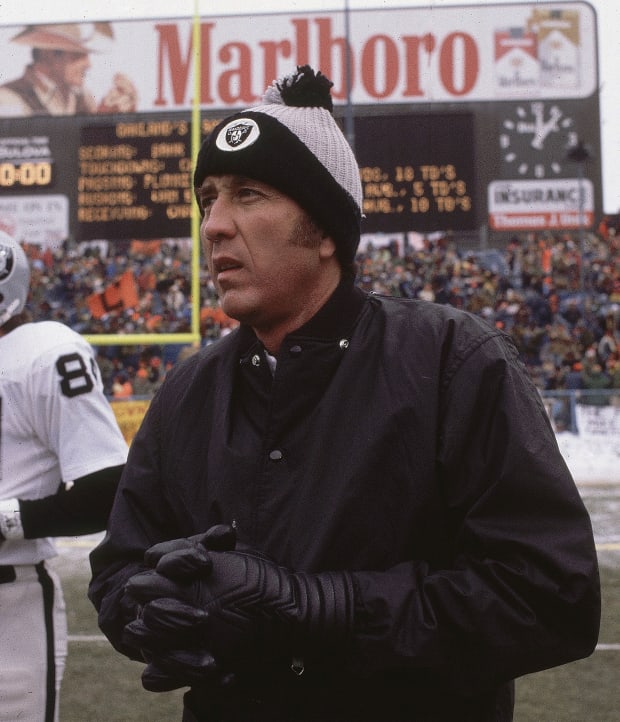

Tom Flores will finally be enshrined in the Hall of Fame, which leaves only one question for the coach and his players: What took so long?

Dressed to the nines, surrounded by family and friends at a hotel in Atlanta, Tom Flores waited for the knock.

When he’d open the door, David Baker, the

unmistakably large president and CEO of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, would welcome him to Canton, Ohio, letting him know that he’d forever be immortalized as one of the game’s greats. Then, that night, he’d be formally introduced as an inductee of the class of 2019 and be welcomed with long-overdue applause from the game’s brightest stars at the NFL Honors ceremony. He’d spend the next day watching Super Bowl LIII while shaking hands, overwhelmed by the sheer number of old friends eager to congratulate him in person.But none of that happened. Instead of Baker and a camera crew, the phone rang to let Flores know he didn’t make the final cut. What was supposed to be a party felt more like a wake. He went to the NFL Honors that night and watched as yet another class of hall of famers walked on that stage before him—the 20th time he was passed over.

“I was sure two years ago I was in,” Flores says now. “I got so close before I kind of got discouraged. It bothered me quietly. I couldn’t make noise about it because that wouldn’t have gone over too well. Some guys can make noise about it because that’s their personality, but it would’ve been way out of character for me to do that.”

Flores has four Super Bowl rings to his name, earned over the course of an epic pro football career that spanned 36 years. Hispanic communities consider him a trailblazer in the sport—he was the first Hispanic quarterback in pro football history, the first Hispanic head coach in NFL history, and the first minority head coach ever to win a Super Bowl. He was first eligible for the Hall in 1999; despite his résumé, getting overlooked became an annual tradition that he and his former players grew accustomed to.

On a Sunday afternoon in January, the Raiders asked Flores to take part in an interview for what they said was a documentary. Sitting in his Indian Wells, Calif., home that day, he heard six quick, booming knocks at his front door. His wife, Barbara, answered but quickly came back inside to tell him some people wanted to see him. Confused, Flores grabbed his cane and shuffled his way to the foyer, where he could see a hulking figure filling his entire doorway.

Ken Herock still remembers the play. Lining up against the San Diego secondary, he was supposed to go deep along the right sideline, but he knew the defense would be draped all over him with the coverage they were showing. So, he decided to improvise and stop short to give his quarterback a better chance. Sure enough, his QB threw the ball deep, landing incomplete with no receiver in sight.

“Oh my God, I heard about it when I got on the sidelines,” Herock recalls. “I ain’t going to get into it, but let’s just say he got after my butt. You knew when you’d screw up you’d get that Tom Flores look.”

Before he was a coach, Flores was a quarterback. A two-year starter at the College of the Pacific, he settled for a stint with the semi-pro Bakersfield Spoilers after getting cut by CFL (Calgary) and NFL (Washington) teams. A new league offered his first opportunity to play professionally—in 1960, the American Football League’s inaugural season, Flores became the starting quarterback for the Oakland Raiders. Born in Sanger, Calif., to parents who immigrated from Mexico, he was the first Hispanic starting quarterback in pro football. It was the first barrier he broke, but not the last.

Over six seasons in Oakland, Flores built a reputation for being cool under pressure, christened The Iceman by teammates. Herock, who was a tight end with the Raiders from 1963 to ’66, saw it time and time again in how Flores handled himself in the pocket. “He took so many hits,” Herock says. “I’ve seen him get hit, get knocked out, get back up and get back in the game. He would stand to the last [moment] to get that ball thrown off.”

That demeanor carried over to the locker room, where Flores earned a reputation as a leader, if not a vocal one. “You knew when this guy talks you better listen,” says Herock, who adds that the nickname took on a new meaning over the last 20 years. “He stood in that line, to be able to get that [Hall of Fame honor], same way he did as a player—standing in that pocket.”

Over the past two decades Herock, like so many from those Raiders teams, waited and watched in bewilderment for his quarterback to get the call to the hall of fame. But he never saw a hint of resentment from Flores. “Tom is the kind of guy that doesn’t let things like that bother him,” Herock said. “He doesn’t show it as much. He was very calm about things, you see the Iceman was calm.”

Flores was traded to the Bills in ’67 and spent the final year of his playing career with the Chiefs, serving as a backup on the team that won Super Bowl IV in 1970, before transitioning to coaching.

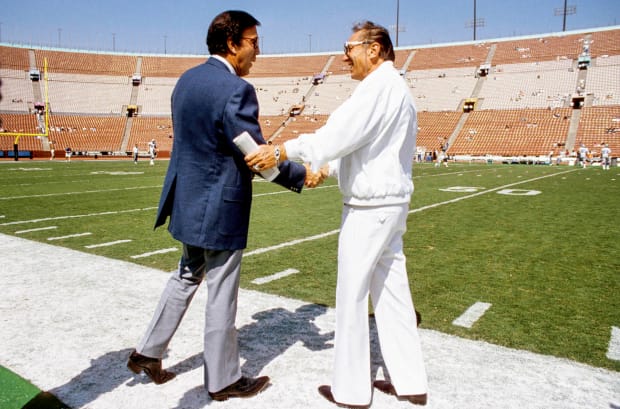

After one season coaching the quarterbacks in Buffalo, he returned to the silver and black, joining John Madden’s staff as a receivers coach in ’72. Flores won his first ring as a coach as an assistant for those Madden Raiders, who beat the Vikings in Super Bowl XI at the end of the ’76 season. Mike Siani, an Oakland wideout for six of Flores’s seven seasons coaching the position, saw Flores as a counterbalance to Madden.

“He was not the yeller and screamer; John [Madden] was the screamer. He would jump all over you if we needed that,” Siani says. “Tom was a teacher. He didn't get riled, he didn't get rattled, he didn't yell and scream at you, he certainly didn't belittle you. He was just the opposite, he was an encourager.”

Fittingly, Flores spent one offseason in Oakland as a junior high substitute teacher, further building his tolerance for students who act out. Siani’s favorite memory of Flores came off the field during one training camp. Siani was roommates with Phil Villapiano, who would go on to become a four-time Pro Bowl linebacker. One night the two decided to sneak out past curfew. They strolled into a bar in Santa Rosa, Calif., only to run into Flores and a few other assistants. Already realizing they were in trouble, the two sat down and had some beers with their coaches.

Of course, Madden found out. Siani recalls Madden saying something along the lines of “O.K., you already f---ed up. You got caught. This is your fine. Now let’s get back to work.”

That team touted future hall of famers in Fred Biletnikoff, Willie Brown, Dave Casper, Ray Guy, Ted Hendricks, Art Shell, Ken Stabler and Gene Upshaw. Siani was also on that team, and celebrated like so many of Flores’s former players when he heard of the news of his induction.

“Finally, finally, finally, finally, the NFL, the hall of fame are giving this guy his due,” he says.

Madden retired after the ’78 season and Flores succeeded him, becoming the first Hispanic head coach in NFL history. In those days the Raiders were known for being on the wild side. The locker room was filled with big personalities and freakish athletes whose immense talents were rivaled only by their testosterone.

“We enjoyed the teammates we had; it was great,” says Rod Martin, a linebacker who played 12 seasons for the Raiders, including all of Flores’s nine seasons as head coach. “And some of them were a little out there—a lot of them were way out there.”

Flores was the perfect man for the job. Not because he kept them in line with an iron fist, but because he let them loose just enough.

“He let everybody be who they were, and he kind of pulled them together,” says Matt Millen, a Raiders linebacker from 1980 to ’88. “That was not an easy task with those teams, because we had some really strong personalities in that group. How should I put it? That was a rogue group.

“He never overreacted to anything. So, when Tooz [defensive end John Matuszak] decided to pull out his .44 magnum and point it at some guys and everybody laughed because they thought he was joking, then he turns around, shoots a stop sign and blows it away—Tom was just like, ‘O.K., yeah, put it away, Tooz. Let’s go.’”

There was a moment during Millen’s rookie year when he came off the field after a mistake and screamed at Flores out of frustration. In response, Flores didn't go up a single decibel.

“I came to the sideline and Tom said ‘Hey, what's going on out there,’ and I screamed back at him,” Millen says. “I mean, I screamed back at him and he said, ‘Hey, calm down.’ I told him to shut up or something. And Tom just looked at me and said, ‘It's a game, calm down, you'll be fine.’ And that was it; he let it go.

“Ted Hendricks was standing next to me and he goes, ‘Rookie, that's a good way to get your ass cut.’ ”

That's just who Flores was, and there’s no denying that it worked. In just his second season as head coach, the Raiders won Super Bowl XV, the first wild-card team ever to do so. Flores became the first minority head coach to ever win a Super Bowl, and Jim Plunkett became the first minority to quarterback his team to a Super Bowl win—to this day, Plunkett is the only Hispanc player to be named Super Bowl MVP, throwing for 261 yards and three touchdowns in the victory over the Eagles.

Flores is one of the most iconic Latin figures in sports—coaching a team with a massive Hispanic fan base. But Flores says he never really saw himself any different from his peers, that his ethnicity was never a topic of conversation until the recent social justice movement that highlights and empowers cultural identity.

“It didn’t really come up that much,” Flores says. “It seems to be coming up more now because of all the emphasis on Black Lives Matter movement. Ethnic issues … it seems like they’re so much more prominent than they ever have been. But it never was an issue when I was coaching, when I was playing.

“Growing up in California, I never felt it [racism]. There was a little when I was in high school, junior high, but those were small by comparison. It was nothing like you had when we went down south where they were not going to feed Black players.”

Hall of Fame cornerback Mike Haynes admired Flores for many reasons, but his background held a special significance for him. Whether Flores knows it or not, just his success as a Latino paved the way for countless Hispanic players and coaches in the NFL.

“I grew up in Los Angeles, pretty close to East L.A.,” Haynes says. “I grew up with a lot of Hispanic kids and Asian kids, and grew up during the Civil Rights Movement. It was gratifying to have him as a coach, and know what he added to the diversity pool and the opportunity for non-white guys to get a coaching job in the National Football League; I think was great.”

Haynes still views Flores as an inspiration. When he was traded from the Patriots during the 1983 season, he viewed Flores as a godsend.

After their Super Bowl XV win, the Raiders failed to make the postseason in ’81 and fell short of the playoffs in the strike-shortened ’82 season. So they added a game-changer in Haynes, and it was nothing short of a culture shock for the star corner, who was used to players being berated for any misstep. He was thrown for a loop when a teammate showed up so late to a Raiders film session that it was just about over and wasn’t chewed out in front of the entire team.

Another time, he watched as a fight broke out between two teammates during a practice in October. Haynes had seen fights during training camp, when players are trying to make the team and emotions run high, but he’d never seen a fight break out during a midseason practice. Flores didn’t immediately break it up. And when Haynes returned to the locker room, the players who were fighting were playing cards together. It became apparent that he wasn’t in New England anymore.

“I had an appreciation for it,” Haynes says, “‘Wow they treat you like a person here.’”

Haynes, who had never played in an AFC championship game up until that point, remembers the last practice before the Raiders faced Seahawks with a Super Bowl trip on the line. He was expecting a big, theatrical speech from Flores. “I’m thinking I’m finally going to hear the speech that I’ve been waiting all my pro career to hear,” Haynes says.

Instead, like always, Flores rounded up his players at the end of practice and told them what they needed to hear.

“Tom said something to the effect of, ‘Well guys, another big game tomorrow. We’ve played in a lot of big games. This is just another big game. See you at the hotel tonight,’ ” Hayes says. “That’s it?!

“I'm so glad he did it because I think if he would have said, ‘We do this and if we do that,’ it would have caused all kinds of stress and guys probably wouldn't have slept that night.”

The Raiders scored the first 27 points against Seattle and won that game, comfortably, 30–14. One week later, they blew out Washington, 38–9, in Super Bowl XVIII, Flores’s second ring as a head coach and fourth overall. There was no doubt he was leading a dynasty, but the credit he had earned never really came.

Millen, like the rest of Flores’s players, shook his head every time his coach was passed over for the hall, but all those Raiders admired Flores’s stoic demeanor; it was a key to his—and their—success.

“Tom never said a word about it,” Millen says. “That’s the way Tom is. We knew what kind of coach he was, and he was the perfect coach for those teams.

“This is one of the problems with him getting in the Hall of Fame so late. You would go to the game, watch the whole thing and talk about all the guys who had great games and then you’d say, ‘Hey who’s the coach there?’ Tom just faded into the background. It’s a great personality trait that he could still be in charge. Not everybody could pull it off. But he could.”

Eventually, Flores stepped down from coaching and joined the team’s front office after the ’87 season. But he only stayed there a year before joining the Seahawks as their president and general manager. He returned to coaching in ’92 for Seattle and proceeded to go 14–34, getting fired after three consecutive last-place finishes in the AFC West. Despite the Lombardi Trophies and stellar 8–3 postseason record, and the fact that he and Mike Ditka remain the only people to ever win a Super Bowl as a player, head coach and assistant coach, that run in Seattle would, for many, tarnish his Hall of Fame résumé.

Why was the wait interminable, and why is it over now? Getting elected into the Pro Football Hall of Fame is no easy feat, and neither is grasping its selection process.

Over the years, it became increasingly difficult for coaches and older players to be selected because they were typically going up against more modern players just becoming eligible. They were overlooked in favor of the game’s more recent stars.

So the Hall of Fame formed several subcommittees for selecting coaches and senior candidates separate from the traditional player pool. Coaches, just like players, need to be retired at least five years to be considered, and to be considered a senior candidate your active career must have been over for 25 years. (Additionally, a contributors category was created for those who contributed to the game of football outside of playing and coaching, such as front office executives. They are selected completely separate from the modern-era, coaches and senior categories.) Candidates go through continuous preliminary rounds until the final meeting—the day before the Super Bowl—where they are narrowed down to just one finalist for each of the three categories, then are voted in and need an 80% yes vote.

This is the first year the Hall of Fame is using this format—on a probationary basis until 2024. Drew Pearson was selected as a senior, Bill Nunn as a contributor and, 22 years after he first became eligible, at age 84, Flores as a coach. There were a few reasons for the long wait, the first being out of his control.

The team Flores coached was loaded with talent and Al Davis, the Raiders’ legendary owner and general manager, received most of the credit for their success, rather than the soft-spoken head coach.

“Mr. Davis was bigger than life, so to speak,” Plunkett says. “He was always at the microphones. And I think coaches under him tended to be overlooked because he was the mastermind behind the whole thing.”

Those on the selection committee were well aware of the narrative as well.

“A lot of people felt [the Raiders’ success] was the product of Al Davis more than anything,” says Howard Balzer, a veteran NFL writer and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame selection committee who now manages FanNation’s All Cardinals site.

Davis and Flores undoubtedly had a good friendship and found success working together, but Flores admits that this perception bothered him, and he wasn’t the only one.

“I can tell you what I heard: They think Al was running the team and not Tom,” Haynes says. “Every time I heard that it used to really upset me because I'd say, Look, Al Davis never came into the locker room at halftime. He was never in the locker room before the game giving a pre-game speech, he never called a meeting and called the team up to talk about this, that or the other. This was Tom’s team.”

Some voters, including former Colts president Bill Polian, felt that working under Davis was actually a positive for Flores’s case—it wasn’t a job just anyone could do.

“He essentially remade the team on the fly working for Al Davis who—while a phenomenal football man—was also a difficult person for which to work because he was so hands-on,” Polian says. “A difficult guy to coach for.”

But the one criticism that appeared to hinder Flores’s Hall of Fame case the most was his stint in Seattle.

“If you throw out his years in Seattle he's definitely a Hall of Fame coach,” member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame selection committee John Czarnecki says. “I have no qualms about voting for him, but I know there were a lot of guys who still held the Seattle thing against him.

“I was sort of surprised that he got the final vote. It seemed like there were so many people in the middle of the road, you never know how the room’s going to vote.”

Multiple selection committee members acknowledged that Flores’s time in Seattle hurt his case but virtually all of them added that it was not a well-run organization at that time, under the ownership of partners Ken Behring and Ken Hofmann. Still, those three seasons are likely what kept him out of Canton for so long. That includes 2019, when he made it to the final 15 and felt sure he was getting in. When he didn’t, he was so hurt that he skipped the Super Bowl the next day and returned home, ultimately unsure if his day would ever come—until it did.

It wasn’t in a swanky hotel or the day before the Super Bowl, but it was his day. Baker waited for Flores at his doorstep to give him the news he’d waited to hear for so long. A wave of 22 years in the making suddenly washed over him.

“Teary-eyed, breathtaking joy all in one sense of emotions,” Flores says. “I was at a loss for words.

“This is a reward. Finally, some people have recognized and acknowledged what I’ve done and hopefully what I’ve done as a coach—and not just because of popularity or something like that.”

So, this Sunday, Flores will get his moment on stage with a gold jacket and a bronze bust. A pro football career that spanned four decades and he never wavered. He didn’t complain, didn’t break under pressure and waited for his turn.

It’s just like The Iceman to stand in the pocket and wait.

More NFL Coverage:

· Meet David Baker, the 400-Pound Man Who Is the Face of the Hall of Fame

· SI Vault: Tim Brown Always Stayed Cool

· The MMQB All-Time Draft

0 Comments