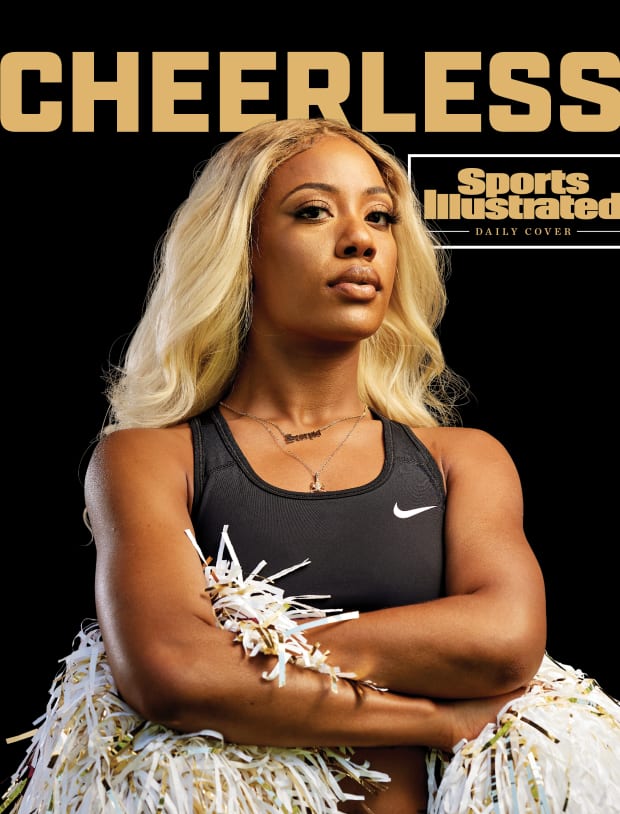

Change was needed after years of mistreatment. But as teams try to ‘fix’ cheerleading, the women are often cut out of the conversation.

The email showed up at 3:29 p.m. on a Friday in February. In 31 minutes, there would be an “Important Meeting”—the only two words in the subject line of a Washington Football Team executive’s email.

Candess Correll decided she wouldn’t be joining the Zoom call. She was a team captain for the First Ladies of Football, Washington’s cheerleading squad for the past six decades, but she’s also a full-time senior software engineer who was working remotely at the time. The short notice was “rude and unprofessional.”

Soon after, teammates filled her in on what she missed: A four-minute webinar during which a team executive, his screen blacked out, told everyone in attendance that the First Ladies of Football would be put “on pause.” Everyone in attendance was on mute for the entirety of it—no one was given the opportunity to ask questions. For all intents and purposes, Correll, her teammates and their director, Jamilla Keene, were out of jobs.

Correll, despite her status as a team captain, says she was “just as in the dark” as everyone else. “It sucks as a leader when you don’t have answers for your teammates and the people that look up to you,” she says.

The NFL has become increasingly inclusive for women on the football side. In the past six months, Tampa Bay Buccaneers assistants Maral Javadifar and Lori Locust became the

first women to win Super Bowl rings as coaches; Kelly Kleine (in Denver) and Catherine Raîche (Philadelphia) ascended to front-office positions never before held by women; Sarah Thomas, the first female official in league history, was the down judge at Super Bowl LV; and Maia Chaka became the first woman of color hired as an NFL official.For cheerleaders, though, the progress has looked different. Over the past few years, franchises across the league have moved to rebrand, redefine and reimagine cheerleading after years of low wages, lacking diversity and sexual harassment. But one important voice has been cut out of the conversation: the women themselves. Which raises the question: Is this truly progress for NFL cheerleaders—or is it just meant to look like it is?

The image of the NFL cheerleader—hot pants and go-go boots—is rooted in objectification. During a Cowboys game at the Cotton Bowl in 1967, a stripper going by the name Bubbles Cash drew fanfare when she strutted down the aisle wearing a short skirt, two cotton candies in hand. Team president Tex Schramm took notice and began to consider alternatives to the co-ed high schoolers on the Cowboys’ sidelines. When Dee Brock, the team’s cheerleading director, pointed out that models—Schramm’s first choice—can’t dance, trained dancers filled the roles. The uniforms began to change in 1970, and within two years the look had become what it is today.

NFL cheerleading has evolved since then. Today, most cheerleaders are high-performance athletes who train their entire lives to be on a squad. They dance during the pre-game and every time music comes on over the course of a three-hour game. During the season and offseason, they make community appearances and participate in private corporate events. Because the cost of attending an NFL game is prohibitive for many, cheerleaders at community events are often the closest fans will get to a game day experience.

“I honestly joined because of the USO tours and a lot of the community outreach events,” says Melissa Wallace, a Cowboys cheerleader from 2014 to ’17.

Wallace was a competitive dancer her entire life, spending seven days a week in the studio. NFL cheerleading was a way to continue dancing after high school; the community and team appeal played big roles too. “I’m from Las Vegas, where previously we didn’t have any sports teams, so it was not really a ‘town’ feel. Coming [to Dallas] and having everybody so excited about the Cowboys was really cool for me and I wanted to be a part of it.”

For all those positives, working conditions, historically, have been problematic. Pay is exceedingly low considering the time commitment and the enormous amount of revenue NFL franchises generate—most cheerleaders are paid minimum wage, or just above. On game days, they often have to arrive at the stadium four to five hours ahead of time to practice and get ready (time for which they are paid). They are also compensated for, typically, 12 to 15 hours of practice per week during the season. Most work or go to school. One former cheerleader, who agreed to speak to SI only under the condition of anonymity, says fast-food workers made more than she did as a cheerleader in 2018.

“I know [employees at] the Steak ‘n Shake down the street made $11 an hour,” she says, “and I remember thinking, my rookie year, ‘I make $8 an hour; I work steady hours and I only make $8.’”

Low wages and poor treatment often lead to a feeling of disrespect. In the past decade, several former NFL cheerleaders have sued over wage theft, unfair treatment and a toxic work environment. Erica Wilkins sued the Cowboys for wage theft in 2018 (the suit was settled out of court); Lacy Thibodeaux-Fields was one of two cheerleaders to sue the Raiders for wage violations in 2014 (also settled out of court); Maria Pinzone sued the Buffalo Bills for wage violations, alleging poor working conditions, that same year (still ongoing, a spokesperson for the Bills did not respond to multiple emails requesting comment); Kristan Ann Ware sued the Miami Dolphins for discrimination, and Bailey Davis filed a sex discrimination complaint against the Saints with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2018. Ware, who believes her workplace turned hostile after she opened up about her religious beliefs, and Davis offered to settle their lawsuits for $1 in exchange for a meeting with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Anna Isaacson, the league’s senior vice president for social responsibility, and league lawyers took a meeting with Ware’s lawyer, but Goodell didn’t. The NFL leaves the management of cheerleaders up to individual teams.

“If Roger Goodell just invited us to the table and literally said, I am willing to work with the women who so bravely spoke out about the injustices and the mistreatment in the NFL, if the NFL changed how they treated women, [can] you see how the rest of the world would follow suit?” says Ware, who dropped her lawsuit. (A league spokesperson did not respond to multiple emails requesting comment for this story.)

You can also find cheerleaders who are perfectly happy with their employer and compensation. That’s in part because, with franchise’s handling their own squads, pay, time commitment and overall treatment vary. Emma Hess, a former Minnesota Vikings cheerleader, says she and her teammates were “lucky” because they were paid Minneapolis’s minimum wage, $11.25 per hour, instead of Minnesota’s minimum wage, which was $9.86. Sponsors typically allow cheerleaders to receive free or discounted services, like nails, hair, tanning, and more.

Increasing cheerleaders’ wages wouldn’t be an act of charity. Melanie Coburn was part of a past era for the Washington Football Team, as a cheerleader from 1997 to 2001 and the team’s marketing director for the First Ladies of Football from 2001 to ’11. She says during her time as marketing director, the squad’s revenue grew from $20,000 to more than $300,000 annually through paid appearances and sponsorships. She says the team could have afforded to pay the cheerleaders more, which she estimates was about $50 per game during her time with the franchise.

“I think [the team thinks] cheerleaders are disposable and they can find other women to replace them and that they don’t deserve [a better] wage,” Coburn says.

Along with sponsorships, most squads sell a calendar of cheerleaders as another source of revenue—and some require the cheerleaders to buy and sell their own calendars. (Correll, for instance, says she bought the First Ladies of Football calendars for $25 each and sold them to friends, family and fans for $50.) Wallace says that while she was compensated hourly for her time shooting the swimsuit calendar, she and her teammates didn’t see any of the profits (the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders publish five formats of calendars each year). When she wanted to give her mom a calendar, she had to buy it herself.

“I’m buying a calendar with me on the front of it,” Wallace says. “We do get a free paid trip to Mexico or wherever they do the shoot, so I’m not saying it’s completely [bad], but I think there are some things that could be tweaked to make it a little bit easier on the girls, [so we’re] not so stressed about money.” (A Cowboys spokesperson did not respond to multiple emails requesting comment for this story.)

One former cheerleader says she wasn’t upset that she didn’t earn any profit from the calendar because she was just happy to “make calendar.” However, shooting the calendar—which required “upholding rigorous diet and workout regimens, being uber aware of your physical appearance and how marketable you were,” she says—was so stressful that she hasn’t been back to the beach since.

“I loved the team bonding [during shoots],” she says. “I am very grateful for the all-expense paid trips, but as an introverted individual who had to balance school with shoots, scheduled activities, camps, appearances, dinners, along with all the psychological and physical stressors of the two weeks, I am not so sure if given the opportunity again I would be as blinded by the glamor. I would have to factor in the anecdotal evidence before considering if it would be willing to go through something like that again.”

The most serious issues though, relate to sexual harassment. “The number of strangers who have touched my butt at professional corporate events is frightening if I think about it for too long,” says one former cheerleader.

That cheerleader’s squad had security on hand that would step in as soon as she gave them a look or tensed up. For another former cheerleader, she says her squad’s “security” at community events amounted to a few marketing interns—they couldn’t do anything when a fan touched her.

The pause put on the First Ladies of Football came less than six months after the Washington Post reported in August that former WFT cheerleaders appeared in lewd videos, made up of outtakes from the 2008 and ’10 swimsuit calendar shoots, without their consent. The Post also reported that Tiffany Bacon Scourby, a former First Lady of Football, accused team owner Dan Snyder of suggesting she join his friend in a hotel room so they “could get to know each other” during a 2004 charity event. (Snyder denied that allegation in a statement last summer; two Washington Football Team spokespeople did not address questions from Sports Illustrated regarding the Post story.)

The men harassing the cheerleaders are the problem. But, Correll says, the cheerleaders are the ones being punished.

“I think that the men that are at the seat of this table that are making these decisions are like, ‘Hey, it’s just easier to remove the program, remove the opportunity of us mistreating these women. So instead of deciding to treat them fairly and equally and as humans, we just get them out of our sight.’ ”

The Washington Football Team recognized it had a problem. Over the past year it’s made wholesale changes to the front office, including the hiring of new team president Jason Wright in August.

Washington confidentially settled lawsuits with a group of cheerleaders who appeared in the lewd calendar-shoot outtake videos. And they hired Petra Pope to evolve a new coed cheerleading squad.

In media appearances, Pope (whom Washington did not make available for an interview for this story) has used the terms “athletic” and “inclusive.” According to information provided by the team, Pope’s coed squad will consist of “nearly 40 dancers, gymnasts and stunters,” approximately two-thirds of whom are women. They say every former cheerleader who tried out made the team, and that “almost half” the squad is former First Ladies of Football. (There were 36 women on the 2020 squad.)

This isn’t Pope’s first time stepping in for an embattled franchise. After a Milwaukee Bucks dancer sued the team for wage theft in 2015 (the case was settled), the team brought in Pope to revamp the squad. Other NBA dance teams followed suit, combatting an image of cheerleaders some executives thought wasn’t “family-friendly.”

Several NBA dance teams went from all-female squads who performed in crop tops to coed hip-hop squads performing in athleisure wear. Several dancers publicly opposed the changes at the time. The changes were made in response to the #MeToo movement, but many women view the solution—and management’s attitude—this way: Women can’t complain about workplace culture if they are not in the workplace.

“That has a lot to do with this country and the sexism and how women are treated to begin with,” says Sierra Martinez, a former Miami Dolphins and Raiders cheerleader. “It blows my mind ... It makes no sense why we’re the ones having to change everything about ourselves to conform to what they think is the issue—which is them, really.”

Some NFL cheerleading squads have been undergoing a more subtle rebrand in the past couple of years that attempts to show the cheerleaders in a new light. Vikings cheerleaders have phased in long leggings in place of shorts skirts, and instead of a swimsuit calendar, the women pose in gyms. Taylor Fondie, a Vikings cheerleader from 2016 to ’19, says the rebrand happened around ’17.

“A lot of people misconceive [cheerleading] as very sexualized … [the Vikings] wanted us to be perceived more as athletes,” she says. “What we do is hard work. A lot of us grew up doing dance, and dance and cheerleading are a sport. I know a lot of people like to argue it, but the workout routines that we go through, a lot of people would struggle to do something like that.”

At the end of 2018, Indianapolis Colts cheerleaders went through its own rebrand when the squad wiped its Instagram clean and posted about the #CCNextChapter.

“This approach is designed to elevate the Colts Cheerleaders as one of the top cheer and dance squads in the NFL by departing from many of the stereotypes often associated with professional cheerleading and redefining what it means to be a cheerleader and an athlete-performer,” one caption reads.

The rest of the Instagram feed is filled with images of cheerleaders on and off the field to showcase that they are more than shorts skirts on the sidelines. They are engineers and doctors and mothers.

Fondue says the Vikings wanted women on the squad who could “represent the brand” and speak to people on “a personal level.”

“I think that’s really important,” she says. “It shows fans, the audience, and people out there that we’re humans too. We have a lot to us. We can connect and talk about football and you’ll be pretty surprised. We know our stuff. We’re not just on the field to look pretty.”

Other teams, like the Titans, have added men to their squads and replaced stylized pom dancing with more traditional cheerleading. Martinez says the Dolphins cheerleaders went through a rebrand, where go-go boots were replaced with heeled sneakers and the cheerleaders’ cleavage was covered up.

Mhkeeba Pate, a former Seattle Seahawks cheerleader who now hosts the Pro Cheerleading Podcast, says the rebranding efforts strike her as “forced.” While she doesn’t think it’s bad to highlight the women’s other achievements, cheerleaders should not be burdened with having to respond to someone’s narrow viewpoint that they are just sex symbols.

“We’re not what needs to be fixed; it’s the mindset that needs to be fixed,” Pate says. “If we stop holding on to that false narrative and really feeling like we have to react to it at all times—like changing uniforms, toning this down, changing the essence of who we are—I think we can really have the freedom to express ourselves.”

A look at the NBA gives a sense of what’s coming next. One current NBA dancer who worked on both her team’s all-female and coed squads, and who agreed to speak to SI under the condition of anonymity in order to avoid professional repercussions, says she tried out for her team’s coed hip-hop squad after spending a year on the all-female squad because by the time the team announced the change, it was too late for her to try out somewhere else.

Men were added to the squad, and the appearance of the dancers, as well as the dancing style, changed. Instead of stylized jazz, the dancers were expected to perform hip-hop and tricks.

The pay stayed the same, she says, but instead of practicing nearly every night, she and her teammates practiced just once or twice per week. Community appearances nearly stopped and, she says, because of the change to their attire, fans didn’t recognize the dancers in the arena.

“It was like, well, if we get rid of the all-girl teams and then we won’t have to worry about any factor of being accountable for lower wages or anything along those lines,” she says. “And I feel like in this era, what was labeled as something so progressive and inclusive implied that the [female-only] teams were not [progressive and inclusive]—and that’s definitely not the case.”

While the rebrand might seem like a move to uplift the women, many cheerleaders feel like NFL and team executives don’t respect them. Cecile Nguyen, a former First Lady of Football, says that feeling was amplified when Washington Football Team executives didn’t ask the cheerleaders for their input or perspective before firing them in the middle of the workday with 31 minutes notice.

“No matter how many videos we take to talk about the important issues in the world and share our perspective, no matter how many times we post or share about the workouts that we do, the fitness regimens that we do and how to guide other people, no matter how many routines that we put out there that showcase our different styles and different technical skills, like doing fouettes on the field and aerials and tumbling on the field, no matter how many times we talk about it and have shared that through interview, through word of mouth, through the magazines we’re written, through articles, through blog posts, through everything, I don’t think that they really understand who we are,” Nguyen says.

In 2014, five former members of the Buffalo Jills—then the Buffalo Bills’ cheerleading team—filed a lawsuit alleging wage violations and poor working conditions, such as holding them to a high standard but not paying them as employees. Stejon Production Corp., the company that managed the squad, suspended all cheerleading operations (the case is featured in the documentary A Woman’s Work: The NFL Cheerleading Problem). Seven years later, the lawsuit has not been settled and the Jills have not come back.

“I knew as a Buffalo Jill what was going on and what I had seen was not right, not appropriate, not proper,” says Maria Pinzone, one of the plaintiffs. “Anytime I have any kind of doubts or feel sad or upset about there being no team … I feel horrible about that, but I am not the reason that happened. They chose to handle the situation in that way and that’s on them.” (A Bills spokesperson did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and a voicemail left at the number listed on corporate filings for Stejon Production Corp. was not returned.)

A you-are-replaceable mentality seems to be a theme throughout a lot of NFL cheerleading teams, but America gets a glimpse into it with the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. CMT’s Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders: Making The Team, a reality show that just finished its 15th season, follows the candidates trying out to become one of America’s Sweethearts. Women are constantly reminded that cheering for the Cowboys is an honor and a job they should be grateful to have. When one training camp candidate made the mistake of saying in a mock interview that she hopes to use her time as a cheerleader to help advance her broadcast journalism career, she was cut from the team’s training camp within a few days. During Season 4, when returning cheerleader Lauren Castillo sat down for her panel interview during auditions, the panel asked her a simple question: “Would you say that you make the uniform or the uniform makes you?” She answered: “I make the uniform because I am fully prepared to come with everything that I have and be a rockstar.”

The judges weren’t happy. “‘I make the uniform.’ Are you kidding me,” choreographer Judy Trammell says to the other judges on the panel after Castillo leaves the room. Castillo didn’t make the team that year.

“The sad side of that is you’re not always told what’s expected of you,” says a former NFL cheerleader, who agreed to speak to SI under the condition of anonymity. “Normally at the end of the job, you have an exit interview or you have a review of stats of how you’re doing and it happened only one time in my entirety of professional dance teams. It’s hard because sometimes they have thoughts about you that you probably could change or could go about differently and you don’t even know that’s what they’re targeting for you, so there are ways for them to manipulate the system.”

Coburn, who judged auditions for the First Ladies of Football while she was their marketing director, says the judges had “no problem” cutting women for speaking out.

“We always felt disposable,” she says. “That’s how they talk about it. ‘Oh, that girl. She’s a tough cookie. She said something about the team; we’re not bringing her back,’ and they just think it’s a dime a dozen and there’ll be a line at tryouts.”

One former cheerleader says that she believes because she spoke up in support of the Black Lives Matter movement last year she had to watch her behavior the rest of the year.

“I was like, ‘If I keep doing this, they’re literally not going to take me back on,’ ” she says. “‘They don’t want trouble. There are 500 girls lining up for a spot on this team. It’s not that hard to get rid of me.’ It’s something I had in the back of my mind.”

With nowhere else to go, cheerleaders often confide in Pate, who typically takes cheerleaders’ main concerns and highlights them on her podcast. Pate has found that alumni cheerleaders often look back on their NFL stints with a critical eye, wondering why they don’t have more to show for their time with the organization. Current cheerleaders, though, often seem just happy to be there.

“When you’re on a team, when you just think about everything that it takes to make the team, there’s just an evolution of emotions and preparedness and your mindset around that opportunity, and it’s so different when you’re just grasping at the opportunity,” Pate says. “It’s something that you work so hard for and you are so grateful for and excited about. You just have this mindset that, really, this is the best thing in the world. I think that part of the experience and that high of reaching your goals and having all your hard work pay off is probably more of the driving force.”

Alumni cheerleaders like Pate and Amanda Ross, who was a Ravens cheerleader and is a current union organizer, are eager for the current cheerleaders to unionize. Not only might a union have prevented the abrupt end for the First Ladies of Football, it also would give the cheerleaders consistent standards across the league. Each team has different perks. For instance, Martinez says Raiders cheerleaders had personal nutritionists and dieticians working with the women to help keep them in top shape for their body type. The Dolphins didn’t have that; instead they had a women's empowerment series during rehearsals, where motivational speakers were invited to practice.

Any employee can unionize, but where it gets tricky with NFL cheerleaders is that some are hired as independent contractors, allowing the team to not officially employ them but still tie them to their employee bylaws.

“I think it speaks to, [teams] don’t really value cheerleaders,” Ross says. “I think they just want us to do what they want us to do, and not complain about it and be that pretty face on the field.”

One former cheerleader says she doesn’t think unionizing will ever happen because cheerleaders are expected to not want more. “There’s a pride about the legacy and tradition of the team and how the whole experience is extremely glorified, where you’re supposed to be really grateful to be there,” she says. “And honestly, it was a dream come true for me. It is amazing. I don’t think it’s perfect and I don’t think it fits every woman. The thought of unionizing, I think [cheerleaders] would look at it as being ungrateful.”

Ross believes that lack of knowledge surrounding unions is preventing the cheerleaders from forming one. “I think fear is a really big barrier,” she says. “I think [cheerleaders] recognizing their value as well, understanding that we may not bring in the millions of dollars the players bring in, but we do bring in a substantial amount of money—I mean we’re the ones that are doing all of the community appearances that players don’t always come to.

“But their mentality is a barrier. And education. Knowledge is power—the more knowledge they can have on what unionizing is, and that it’s not a lawsuit and we’re not going to go head-to-head with the league. We’re just asking for a collaborative experience, and that should be offered in every workplace.”

Even with no union to help act on problematic working conditions, cheerleaders have proven capable of taking it into their own hands.

When Drea Lewis, a Black former Broncos cheerleader, was on the team, the squad’s hair sponsor allowed cheerleaders to receive free or discounted services. But the hair stylists were only adept at working on white women’s hair, so Lewis paid out of her own pocket to have her hair done. And Lewis says there wasn’t a game day makeup artist who knew what shades to use to complement Lewis’s skin tone, so she did her own makeup. (In response, a Broncos spokesperson says that “Diversity, equity and inclusion is a priority for the entire Denver Broncos organization, including our cheerleading program … [for the] last several seasons, cheerleaders who elect to receive haircuts at a different salon have been eligible for full reimbursement as part of a formal policy. The concern raised by [Lewis] was never brought to the attention of our staff, which would have immediately addressed it and provided alternative arrangements.” Lewis insists that the team was aware of her out-of-pocket expenses but didn’t offer reimbursement.)

Diversity is a major problem within NFL cheerleading. The Institute For Diversity and Ethics in Sport’s annual NFL reporting which showed that 69% of NFL players in 2020 were men of color. TIDES doesn’t compile data on NFL cheerleaders, but through a survey, Pate estimates that 17% of NFL cheerleaders are Black.

The lack of regulation—the NFL, for instance, has the Rooney Rule to promote consideration of Black candidates for head-coaching jobs, but there is no such oversight for cheerleaders—plus a standard of beauty that emphasizes a white, European look, seems to be the contributing factors, says Sheila Ward, a board member of Black Women in Sport Foundation. Black women are dancing in “safe and affirming places,” like Black colleges and community centers and Black-owned dance studios, she says, but not in the NFL.

“When [Black women] have those national platforms, that’s making people uncomfortable that they have to recognize that you have a group of women that are out there and proud of who they are and how they look and they’re willing to present that to the world and have other young girls and even young boys and men admire them for admiring their beauty,” Ward says.

Says Lewis: “When [a Black cheerleader] becomes part of a team, you feel tolerated because first and foremost, there’s never enough resources to help you win the same way as white cheerleaders. The hair and makeup is one example.”

Now, to help future Black cheerleaders, Lewis runs her own hair company, selling wigs, weaves and extensions to Black women. Eventually she wants to turn it into a nonprofit so Black cheerleaders won’t have to pay out of pocket for quality hair care like she did.

“I want [it so] you don’t have to go flat broke or be stressed or don’t feel good or don’t feel confident because you can’t afford this when there’s not a lot of companies or people that cater to the needs of Black NFL dancers. I want to be that person of contact.”

According to Pate’s diversity survey, the First Ladies of Football were actually the most diverse squad in the league—more than half its cheerleaders were women of color. “If we were part of this [rebranding] process and they gained our input, they would realize that they’ve been improving,” says Nguyen. She adds the organization should have been asking, “How can we support [the squad] to take it to the next level, versus trying to fix the problem when they don’t know.”

Now that the First Ladies of Football have been eliminated, many cheerleaders wonder where their sport stands, and if the NFL will ever value them.

“We are professional athletes,” Correll says. “We are the best of the best. We beat out people to make our college dance teams, we beat out people to get on an NFL field and then, within our teams, we beat out people to become captain. We beat out people to become NFL Pro Bowlers, like myself.

“There’s a lot of work that gets put in by these women before they even put their boots on and carry a pom-pom. The players train their whole lives to put on that NFL helmet. We train our whole lives to put on that boot and step our toes on the NFL field.”

Correll had decided before that February Zoom call that she wasn’t coming back for the 2021 season. She’s O.K. that she won’t be seen on the sidelines this fall. What she wants most, like so many other cheerleaders across the league, is to be heard.

More SI Daily Covers:

• What You Haven’t Heard About the Deshaun Watson Cases

• Alex Smith Healed Enough To Walk Away

• Michigan Football Failed to Protect One of Its Own

• ‘This Should Be the Biggest Scandal in Sports’

0 Comments