The NFL commissioner may be thinking about how his tenure winds down. Being a leader on social issues and righting many of the league’s past wrongs would be a great place to start.

Funny when and how this stuff tends to come out, on a sleepy summery week such as this, at perhaps the time when football is the furthest from our collective consciousness. First,

the league’s agreeing to end the practice of “race norming” during the claims process for brain injuries, which presupposed that Black players had a lower level of cognitive functioning and, thus, had a more difficult time obtaining settlement money and proving that football caused their cognitive decline. And second, the league’s finally encouraging (through a committee created in consult with the NFLPA) limitations on the usage of Toradol, a painkiller that causes intense side effects but was commonly doled out in locker rooms in an effort to shuffle injured players onto the field each Sunday. These two stories are seemingly unrelated, though they both encompass a large part of the dark mass bursting through the NFL’s closet doors.

We are often reluctant to talk much about this because it represents one side of the incredible moral trade-off we make to watch, enjoy and (*raises hand*) make a living off a sport that has, sure, made a wonderful life for a good number of people who may have otherwise pinballed through their adult years with no way to be handsomely compensated for their athletic gifts (or, simply, love of the sport), but also created some truly heinous moments of ethical ineptitude.

Some of those trade-offs: Knowingly, or at least willingly with eyes closed behind hands, creating a culture where players feel so replaceable and scared that they opt to stuff their bodies full of an NSAID that causes horrific internal-bleeding issues rather than take a necessary day off. Following a league that submits to a legal strategy that “insisted on using a scoring algorithm on the dementia testing that assumes Black men start with lower cognitive skills. They must therefore score much lower than whites to show enough mental decline to win an award.” It’s fascinating to think of all the moments in which a human being had to talk themself into thinking that these were ideas that would make their parents proud, that they could confidently explain to their grandchildren when their working days were through.

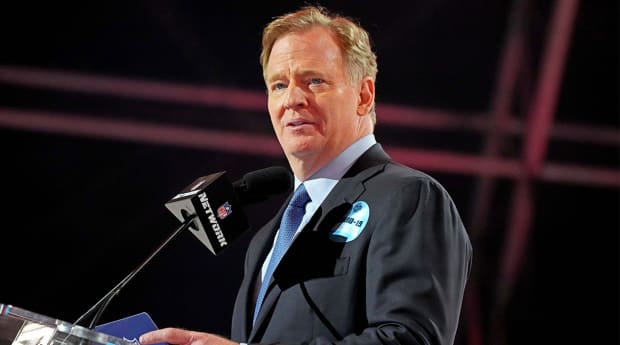

While none of this is solely the fault of the current league administration, and in some ways it’s encouraging to see them begrudgingly coming around on these issues decades after some horrific case studies have arisen or after thousands of former Black players took matters into their own hands (the NFL tends not to back down any other way), it does come at an interesting moment in the league’s own story. MMQB founder Peter King, now at NBC, wrote about commissioner Roger Goodell this week and what might be next for the NFL as his current contract reaches its end after the 2023 season. The tea leaves there suggest he will keep going. That there is nothing else he’d rather do than continue to formulate his legacy and increase football’s status as a financial behemoth (when you put it that way, it sounds more exciting than golf). There’s little doubt there will be some splashy presentation. Some catchy, sweeping opus bent on molding together gambling and fantasy sports and television revenue to ensure that the coffers are so comically full that they’d be able to afford to care for their veteran players with no risk to their well-being (but still opt to fight it, anyway).

But we could suggest something bigger and bolder. Something that football could actually lead the country on, at a time when we seem unable, as a people, to willingly face our own shadows.

What if Goodell spent the remainder of his time reckoning with football’s past? Reckoning with the racism, the lack of concern for player health and safety, the mounting mental health issues and player financial issues for those who were cut loose by the game without a net, unable to function in a different world.

If you’re the NFL, this thought may scare you, but why should it? Everything is already out there, even if it isn’t out there. All the fictionalized, horrific versions of the league depicted in movies and television shows like Any Given Sunday and Playmakers had to come from somewhere. The former was based on a novel written by a former NFL player. The latter was knifed by ESPN after the NFL expressed its disapproval of the dramatic series, which depicted some of the dirt underneath football’s rugs, including drug use, homophobia and chronic injury issues. It’s not like any of this would surprise its audience. We’ve already made the trade-off. We’ve already sold our souls. Player testimonials postretirement paint a grim picture of what should be our sunniest years on this earth, a time when a life’s worth of work and understanding meld together. Instead, there are 30-year-old men grappling with their inability to hoist their kids at the beach. Former giants of athleticism struggling to lift their bodies out of bed in the morning. And that’s just the pain residing in the body.

Again, it’s important to note that you cannot point specifically to Goodell, or anyone in particular, and claim this is all their fault. During his tenure, there has been some small, forced baby steps aimed at tackling race-related issues brought on by the overwhelming disparity between white coaches and coaches of color, or the initial, deafening silence as players were attacked for exercising their right to free speech. In general, when societal attention focuses its white-hot light on the NFL, Goodell has helped steer the ship to some less-choppy water, an imperfect resting place of public acceptability. This, like so many grievous things, happens over time. It is an erosion. Water on rock, over and over, day after day, until a gaping void is left behind. We let a little racism slide until it becomes the cornerstone of a lawsuit defense. We let a few shots of a painkiller slide until, as one player believes, it cost him the functionality of his kidney, leaving him dependent on a random benefactor for a new lease on life.

What a task for the commissioner to undertake. To be even more remorseful and understanding of the labor force that has provided him with his own wonderful way of life, instead of simply inserting himself into the discussion at various points of public pressure and outrage. To set a precedent for future commissioners to act like the moral arbiters they were meant to be, and not as the protectors of some business interest. To confront the things that the league would likely rather stay buried on a lazy summer Friday.

More NFL Coverage:

• Breer: Joe Burrow and the Long Road Back

• Brandt: Adam Vinatieri Was Almost a Packer

• Orr: The 10 Most Interesting Story Lines for the 2021 NFL Offseason

0 Comments